Any doubts I have about identifying Rankin’s North London photo studio evaporate the moment I come across it. Behind floor-to-ceiling glass windows is a spotless white foyer with numerous oversized front covers of Hunger magazine – Chloë Grace Moretz, Travis Barker – imprinted on its walls. There’s also a sculpture of a white gorilla, and a photobooth in the corner. The door is embossed ‘RANKIN CREATIVE’; one of the windows proudly states: ‘QUESTIONING EVERYTHING SINCE 1991’.

Rankin isn’t thrilled about the name Rankin Creative. “It puts too much emphasis on me,” he sighs, but when you’re the most famous British photographer working today, your middle name a literal brand, then the emphasis tends to be on you. “I don’t think I deliberately went out to create a brand,” he says, but regardless of intent, a brand very much exists. The whole building exudes brand: from the dressing room with its photographs of Keith Richards and the Queen (she looks cheerier) to the copies of Hunger liberally scattered on every surface. (Hunger’s office is upstairs; our interview occurs in an adjacent meeting room – glass walled, naturally.)

Let us not forget the upcoming exhibition in Wetzlar, Germany – Leica’s homeland – entitled Zeitsprünge (Leaps in Time), contrasting favoured photographs from the 1990s with more recent work. Many of those photographs were taken not for Hunger but Dazed & Confused, the seminal fashion magazine that Rankin founded with Jefferson Hack. (Please appreciate that Rankin is behind two highly successful magazines, and people still think of him as ‘just’ a photographer.) There’s also an ongoing show in Belgium, Rankin: The Dazed Decade, that showcases his most celebrated portraits from the 1990s; if you can’t make the journey, why not buy the hardcover book.

In one sense, two simultaneous career retrospectives is an odd move for a creator whose momentum has been perpetually forward, eyes relentlessly scanning for new horizons. “When you are a photographer, you don’t look back,” says Rankin. “Time’s always on your shoulder.” If your life is dedicated to capturing moments, you must keep searching for the next one: even as thousands of the past moments you captured are slapped onto magazine covers, reproduced in books, burned into a nation’s cultural consciousness.

Equally, like every great artist, a great photographer is invariably shooting for posterity. “If you are worth anything as a photographer, you are always thinking, ‘Is this picture gonna be the defining picture of that person?’” Ask a successful photographer their best photograph, says Rankin, and you will be told, “the next one.” Or, as David Bailey used to say when asked whether a photograph was any good, “I’ll tell you in ten years.”

Rankin

Rock 'n' Roll Star

Five years ago, I interviewed Rankin for the first time. I was, frankly, a little intimidated by the prospect; an intimidation that stemmed from his prodigious résumé – I mean, look at it – and also the common depiction of fashion photographers as semi-crazed egomaniacs who communicate in shrieks and will fire their assistant for bringing them a cappuccino rather than a flat white. It’s a cliché, of course, but clichés exist for a reason, right?

“It’s weird, isn’t it?” says Rankin when I mention my initial nerves. “Photographers have got this really strange reputation from the movies: they’re lotharios, they’re dictators. Everyone’s gonna be like the character in Blow Up.” He’s used to the misconceptions of his profession, and himself. “Reputationally, I was thought to be a bit of a show off. And I’m just not the person that people think I am. At all.”

He really isn’t. While the black jeans and T-shirt, the expertly styled grey hair, give the impression of a former rocker fallen on wisdom and prosperity, in conversation he comes across more as your favourite uncle or a particularly cool university professor. He’s one of those rare people willing to take an interest in anything and everything; mention a topic or trend and he will not only be aware of it but be happy to offer an opinion, and listen to yours. There is a gentleness to him; indeed (and I cannot believe I’m about to write this about one of the icons of Cool Britannia), even something rather cuddly.

Our discussion ranges from AI to social media to the 1990s to politics to artistic posterity. Talking with Rankin is a little like embarking on a conversational rollercoaster: his mind whirrs off in all kinds of unexpected directions, often lifting you to great heights, occasionally making you feel a little dizzy. (Hold on – the question was about his most challenging portrait subjects? Now he’s sharing his ambitions to use photogrammetry to create a sculpture the size of a house!) It’s quite a ride: exhilarating, insightful and relentlessly enjoyable.

There’s a rather sweet detour into the domestic realm when his wife Tuuli returns a phone call of his, checking on the dogs. The pair are avid dog lovers; she has volunteered at Battersea Dogs & Cats Home, he has donated images to the shelter. They own four: Bandit, Hooligan, Squidge and Beans. (A rescue dog, Bandit was originally called Bailey but Rankin feared people would think he was named in tribute to the photographer.)

The dogs feature early but not as early as Brooklyn Beckham. My 2018 interview with Rankin included some less than complimentary quotes about Brooklyn’s skills as a photographer (he had recently released the photography book What I See). A year later, Brooklyn joined Rankin on an internship: “You got me in trouble,” says Rankin as we sit down for this interview. Oh. Sorry. “It was fine at the time. It was just funny.”

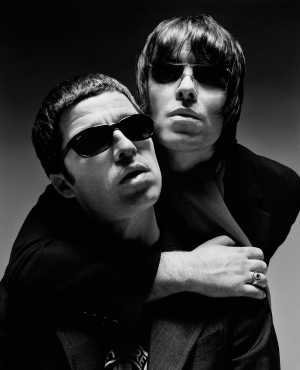

Oasis; Q Magazine, 2002

Rankin

He describes Brooklyn as “a really sweet kid”, liked by everyone in the company, happy to put in the work. “If I was asked the question, ‘What was Brooklyn like?’ I would say, so charming, and a very good photographic assistant. He knows his way around a studio.”

Why did Rankin take Brooklyn on? “I did it because I don’t like people being put in boxes by other people. And I felt that people put him in a box, and I just think that’s unfair. I don’t really care if I get criticised. It doesn’t really bother me. You’re gonna criticise me for helping a kid out?”

Did Brooklyn’s skills improve over his internship? “Do you know what? He did. I thought he was alright as a photographer. We do test shots all the time; he was doing test shoots. You can tell when someone’s got an eye for it. I think he’s just unfortunate that he’s famous.”

Fame found John Rankin Waddle at the zenith of the 1990s, “Everyone telling each other, ‘You’re fucking great! Aren’t we fucking great? We’re fucking great!’” Ambitious kids morphed into jaded celebrities. “We were all bloated – not bloated physically, but bloated in terms of believing the hype. I think everybody believed the hype. At the start of the 1990s, you’ve got amazing music. By the end of the 1990s, you’ve got Keith Allen and Alex James doing fucking Vindaloo.”

Rankin doesn’t absolve himself. “I was a dick,” he cheerfully admits. He viewed his contemporaries as “pop photographers, [whereas] I’m like a rock photographer. At the time I believed that hype. Because when you’re in a bubble, you believe the bubble.” He eventually burst it through fatherhood, therapy and work ethic; even during the headiest times, the work always came first.

“I spoke to Bono about why he thought that U2 were so successful and stayed together as a band, right? He said because they got to go back to Dublin. So if you were in England, you were constantly under that scrutiny. What was different about myself and the other Dazed people was we were absolutely addicted to work.” Any nostalgia that exists is kept well hidden. However, there’s a sense of wistfulness when he notes: “We were the last analog generation. We were the last generation that wasn’t being judged 24-7.”

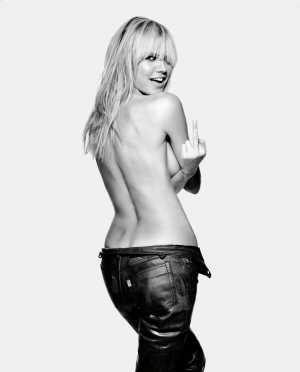

Heidi Klum Italian GQ, 2003

Rankin

OK Computer?

Three Rankin musings on modern society: “It seems to be the thing at the moment: everything is either black or white. I’ve never experienced anything in my life that’s black or white. Everything has grey in it. Anything that we do in our lives has grey in it…

“As I get older, I get more political but I get less partisan. I want to find middle ground more because people are getting so partisan and I find that so strange. I don’t understand it. Like, I don’t understand Kid Rock machine gunning a fucking beer can. [In response to Budweiser’s partnership with the transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney.] That doesn’t make any sense to me. Who fucking cares?

“I don’t want my friends to all just be the same as me. I want my friends to be different and give me different experiences and challenge me and get me excited about stuff that I’ve never been excited about before. I don’t think you should judge someone by their politics, and I don’t think you should judge someone by their opinions. You should be able to navigate that.”

He is no fan of social media yet it clearly fascinates him. In the space of five minutes, he namechecks Things Fell Apart, Jon Ronson’s audio series on the culture wars; BBC 3 documentary The Instagram Effect (“Its founders probably were thinking they were doing a good thing and not destroying the social fabric of society.”); must-watch Netflix docudrama The Social Dilemma; and his own recent project The Unseen, exploring content banned from certain platforms. “Two of the young creators on my team came up with this idea… It’s nuts. The reasons people are being banned are ridiculous.”

Bird Song Hunger, Issue 11, 2016

Rankin

He recalls a shoot in Rome last year. Conversation turned to BeReal, the app that encourages users to share a candid photograph of themselves once a day. A crew member had taken the name of a huge clothing brand as her username. Why? Because if the brand wished to join BeReal, they would hopefully buy it off her. “Be real?” said Rankin. “You are being the least real you could be.” She hadn’t noticed the irony.

In April, the Sony World Photography Award inadvertently gave a prize to an image created by AI. “It was so obviously an AI image,” says Rankin. “How the fuck did they not see it? Are they blind?” I find the image on my laptop for Rankin to inspect. “What the fuck is going on with the hands…? Everything’s very soft in the face…” He notes that every person generated by AI – as opposed to a real-life figure – tends to be conventionally beautiful. “They’ve got very soft skin. They’ve got quite big eyes. It’s really obvious.”

Is Rankin worried for the future of photography? “Of course. You can’t not be. If you love it, you can’t not get freaked out by AI.” Yet he can’t help being fascinated by its possibilities. He mentions Phillip Toledano, a visual artist using AI to make “extraordinary pictures” – obviously fake, wildly imaginative and very beautiful. Indeed the next Hunger front cover will be created by AI. “I need to experiment with it. I can’t not experiment with new technology or I get left behind.”

Ewan McGregor Arena, 2003

© Rankin

Everything will flow

Ahead of this interview, I reached out to five brilliant photographers and friends of square mile: Pip, Lee Malone, Bertie Watson, Kirk Truman and Joseph Sinclair. Might they have a couple of questions for Rankin? Everyone obliged, I put their questions to Rankin and you can read his answers below – which have been edited for clarity.

Pip: How has your relationship with photography – and your subjects – changed over the years?

It’s not really changed because, if anything, I’ve doubled down on my way of working. From a very early age, I wanted to collaborate with my subjects – whether they’re celebrities, fashion models, whoever. I’ve always seen it as a team game. I want to make something together with them. If anything, I’ve got stronger and stronger about that opinion. It’s quite mad how much of a thread there is between what I was doing right at the beginning and what I’m still doing.

Technically, I started going, ‘I’m never gonna be one style of photography. My style is to not have a style.’ And I think I’ve kept that going. I’ve never got lazy and gone, ‘I’m just gonna do this one thing.’ I was always trying to go for something intellectually stimulating and visually stimulating. When I went to the Congo with Oxfam in 2009, this guy said to me, ‘I’m gonna use this picture on my coffin.’ And it really struck me that that’s kind of the picture I wanted to take. Every time.

Kirk Truman: When you take someone’s picture, what are you trying to say?

I’m trying to connect the person with the audience; I’m trying to break the fourth wall. I’m trying to take away the camera between the person and the audience. My intention is for them to be really looking at the audience. Photography is very intimate. When you look at photography, most of the time it’s you and that person you’re looking at. And so I’m trying to break that and make them connect with the audience.

Bertie Watson: Have you ever thought, ‘I’ve fucked up, I’ll never work again!’?

Haven’t thought that I’d not work again. But I have thought I fucked up. I went to Australia with the Australian tourist board in 2003. I was doing documentary photography and I hadn’t done it for a while. I remember thinking, ‘If I jump out of the window and break my leg, I’m gonna be able to get out of this.’ I ended up doing an OK job and I really enjoyed it. But I remember having that imposter syndrome for the last time on that trip.

Nailed it, HUNGER The Beauty Issue, 2019

Rankin

P: Did you intend to create Rankin the brand? Or did that come about organically?

I don’t think I deliberately went out to create a brand. I knew that one name was always gonna be a positive, and I had an unusual name – so I made a conscious decision right at the beginning to drop my second name, Waddle. Initially I wanted to be a collective and call it Untitled and be much more of an art movement – but my ego was far too big for that. What happens with your name is your ego. It pushes your name to the front.

Joseph Sinclair: If you could go back to any period in time and photograph one person, who would it be?

Charlie Chaplin. He was the first internationally famous icon, he was a fascinating character and I am obsessed with early film. Whether it was Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, or Buster Keaton, it wouldn’t really matter; I am fascinated by that period in the late 1910s and 1920s. I find it one of the most interesting periods of time. I’ve just read an amazing book called Hollywood which is a history from then to now.

KT: Who challenged you as an artist the most when taking their portrait?

I can’t really think of anyone challenging. People challenge you. Heidi Klum challenges me: she literally goes, “I want to be on the top of the Hollywood sign and I wanna do this, this and this.” She throws the gauntlet down: ‘Here’s the gauntlet, can you rise to the gauntlet?’ Damien Hirst is somebody that challenges me. The time I saw him before last, he said to me, “You are gonna be a sculptor by the end of the day.” And by the end of the day I wanted to be a sculptor.

He showed me something called photogrammetry, which is a 360 capture of a person, all photographic. He told me to make a sculpture and I did. I can make sculptures now with something called photogrammetry. I’d love to make a sculpture of someone famous. I can bring all of my abilities from photography and take it to photogrammetry. Then you can make a fucking bronze sculpture the size of a house and it’ll last for a thousand, probably ten thousand years. But that would cost me a million quid to do. I’ve got to find someone who’ll give me a million quid to do a house-size sculpture of them.

JS: Do you place expectations on someone before you shoot them?

Never. Absolutely not. I’ve learned the expectations that you place upon people will either blow up in your face, or they’ll be completely different. And I think the people that have really made me realise that include Gordon Brown – like, he was so different from what the media portrayed; I loved him. And Jay Kay from Jamiroquai – just absolutely the opposite of what I thought he was gonna be. And David Bowie! He was like Tigger from Winnie the Pooh.

Ayami Nishimura by Rankin Rankin Publishing, 2012

Rankin

BW: What was it like shooting Robert Downey Jr playing a tuba?

Amazing. Robert Downey Jr is one of the people – when they say ‘never meet your heroes’… I say that’s bullshit. Definitely meet your heroes. Because sometimes they will be so extraordinary. I love Robert Downey Jr. He’s as funny as Ricky Gervais and Ricky Gervais is one of the funniest people I’ve ever met. Both of them are just like: joke, joke, joke, joke, joke, joke, joke. It’s very self-deprecating and it’s very, very, very funny.

Lee Malone: Is AI coming to take our jobs as photographers?

I don’t think it’ll take everyone’s jobs. People like to live in virtual worlds and play games and be avatars – and people also like reality. When I say to you, “Would you like to see a virtual picture of a person or would you like to see the real person?” you’ll probably go, “I’d quite like to see both.” People like to compare them. Some people might like the virtual, other people might like the real thing, and some people might like the difference.

They tried for years to build a computer that could beat a grandmaster at chess. They eventually did it. And even now a master at chess playing with a computer will always beat the computer. It’s another tool to make your work more engaging or whatever. Even now, the AI stuff that you see is all derivative. There are very few people that are using it to create original work. Look at [computer scientist] Tristan Harris’s talk on AI which he did recently. He really gets underneath the surface of it; he’s questioning it much more on a reality level than a hypothetical. At the moment it’s very… we’re experimenting with it. It’s still quite hypothetical.

But can it be a creative outlet? Yeah, anything can be. But what is one defining difference between a great artist and somebody that was just painting or just taking a photograph? The greats brought a perspective within their work that possibly had never been seen or certainly was challenging to the audience. That has to be a human; it can’t be an AI because you have to code in what you want from the AI. So there’s always gonna be a human involved, and that becomes curatorial. And then if you’re curating something, it’s about art, it’s about visual knowledge, it’s about understanding photography. I’ve done it, I’ve gone, ‘I want it to look like a Picasso.’ And they do really good versions of Picasso but that’s not original. That’s me. If there’s no reference, how are you creating something original?

I went to see the Donatello exhibition at the V & A. It’s fucking amazing. He’s in the 14th century and he’s making these reliefs, these sculptures that look like Bernini – which is 100 years later. Donatello is influencing every type of religious image for probably 200 years. He’s still influencing people now. You can create a relief. A relief is basically a 3D version of a 2D image. I’ve gotta do a show now called What A Relief because I love reliefs. That’s inspiring me, Donatello’s inspiring me 600 years after he was making work. That’s amazing. I’m sorry but AI versus Donatello? I’ll take Donatello every day of the week – and that’s 600 years old. I’d rather have a photo of a Rembrandt in my living room than an AI version. It just doesn’t make sense to me.

Crowning Glory Hunger, Issue 9, 2015

Rankin

To the End

We’ve been talking for 90 minutes when one of his team knocks on the door to tell Rankin the lava lamps have arrived. He looks a little confused – lava lamps? Yes, lava lamps – he’s designing a lava lamp for some project or cause.

“Ah,” says Rankin when told this information. He grins at me. “Apparently I’m designing a lava lamp. Would you like a lava lamp?” I would love a lava lamp but there are only two and he needs them for inspiration. I suspect he’ll find it soon enough.

There’s a funny little coda to our interview, entirely unexpected. The very next day, I’m at Somerset House for the Photo London exhibition (as you do). Who should appear to do a book signing but Rankin? I’d say hello but there’s a row of photographers needing to take his picture.

“Say something, guys!” he teases as they snap away in silence. He strikes a few poses, hides his face behind the book. (The Dazed Decades.) Afterwards he shakes each of them by hand.

He sits down, people queue up. The first recipient, a little awestruck, asks if anyone calls him John. “Nobody calls me John,” says Rankin happily. “Only the police.”

It’s a good line, and a good note to leave on. There’s no objective definition of brilliance, but whatever it is, it’s him.

View on Instagram

These photos are taken from Rankin – Zeitsprünge, which is exhibiting until 27 September 2023 at the Ernst Leitz Museum in Germany. See leica-welt.com. For more info, see Rankin